Chinese is the most spoken language in the world with over 1.2 billion native speakers and also one of the six official languages used by the United Nations. Although its not possible to nestle under this article all the bits and pieces of the Chinese language, we would like to share a few things from a translation perspective.

Mandarin vs. Cantonese

The two major variants most commonly known these days are Mandarin Chinese and Yue Chinese (aka. Cantonese). Generally speaking, Mandarin, alternatively called ‘Standard Chinese’, is widely recognized as the de facto language in mainland China and Taiwan. It is also used and taught in primary and/or secondary schools in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. On the other hand, the majority of Cantonese speakers reside in Hong Kong, Macau and China’s Guangdong province. Other variants include Hakka Chinese, Min Nan Chinese, Wu Chinese, Xiang Chinese, to name a few.

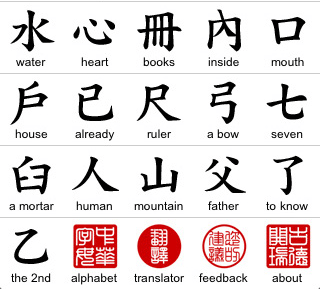

Simplified Chinese vs. Traditional Chinese

Today, the Chinese language is mostly written in two styles: Simplified characters and Traditional characters. Surprisingly, these terms can be a little more confusing than we assume. While the Chinese written language was indeed standardized and its orthography simplified (fewer strokes, more streamlined structure) during the 1950s and 60s as part of the political movement under the Communist Party to improve literacy among the Chinese population, nowadays, the difference between Simplified and Traditional is engraved deeper on a geographic level. The majority of Simplified Chinese users live in mainland China and Singapore, while Traditional Chinese is mainly used by locals in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan and immigrants from those regions.

Cultural Differences and Localization Issues

Lets say you want to localize for the mainland Chinese market a video game with a vicious-looking dragon figure as the ultimate evil boss. Simply translating dragon to its literal equivalent '龙'' may end up interfering with potential users immersive experience as dragon is the almighty embodiment of power and prosperity in the Chinese culture. Another great example resides in the contrasting perception of colours. Common expressions such as red figure and red ink may sound almost counterintuitive for the Chinese audience simply because this particular colour is always associated with something energetic, promising and vibrant.

You might wonder - how do I know which variant and/or script I will need for my translation? And how do I make sure the translation reaches my target audience without causing cultural misunderstandings? Our professional team of Chinese translation project managers and linguists here at ON TARGET will address these concerns and bring you to the specific audience in the most effective way with our genuine understanding of the nuances among distinctive forms of the Chinese language as well as our linguistic and cultural expertise.

Sources: The Chinese Character—no simple matter

Ethnologue.com - Languages of the World- Summary by language size